Kang Sheng (

Chinese:

康生;

pinyin:

Kāng Shēng; c. 1898 – December 16, 1975) was a

Communist Party of China (CPC) official best known for having overseen the work of the CPC's internal security and intelligence apparatus during the early 1940s and again at the height of the

Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A member of the CPC from the early 1920s, he spent time in Moscow during the early 1930s, where he learned the methods of the

NKVD and became a supporter of

Wang Ming for leadership of the CPC. After returning to China in the late 1930s, Kang Sheng switched his allegiance to

Mao Zedongand became a close associate of Mao during the

Anti-Japanese War, the

Chinese Civil War and after. He remained at or near the pinnacle of power in the

People's Republic of China from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1975. After the death of Mao and the subsequent arrest of the

Gang of Four, Kang Sheng was accused of sharing responsibility with the Gang for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and in 1980 he was expelled posthumously from the CPC.

[1]

Early life

Kang Sheng was born in Dataizhuang (大臺莊) (administered under Jiaonan County since 1946),

Zhucheng County to the northwest of

Qingdao in

Shandong Province to a landowning family, some of whom had been

Confucian scholars.

[2] Kang was born Zhang Zongke (

simplified Chinese:

张宗可;

traditional Chinese:

張宗可;

pinyin:

Zhāng Zōngkě) but he adopted a number of pseudonyms – most notably Zhao Rong, but also (for his painting) Li Jushi—before settling on Kang Sheng in the 1930s.

[3]Some sources give his year of birth as being as early as 1893, but it has also been variously given as 1898, 1899 and 1903.

[4]

Kang received his elementary education at the Guanhai school for boys and later at the German School in Qingdao.

[5] As a teenager, he entered into an arranged marriage with Chen Yi, in 1915, with whom he had two children, a daughter, Zhang Yuying, and a son, Zhang Zishi.

[6] After graduating from the German School, Kang taught in a rural school in Zhucheng, Shandong in the early 1920s before leaving, possibly for a sojourn in Germany and France,

[7] and ultimately for Shanghai, where he arrived in 1924.

[8]

Shanghai

After arriving in Shanghai, Kang enrolled in

Shanghai University, a former teacher's college that was officially funded by the

Kuomintang but had come under the control of the CPC and the intellectual leadership of

Qu Qiubai.

[9] After about six months at the university, he joined the Communist Party Youth League and then the Party itself, although the circumstances of his membership and sponsorship remains something of a mystery.

[10]

At the direction of the Party, Kang worked underground as a labor organizer.

[11] He helped organize the February 1925 strike against Japanese companies that culminated in the May 30th Movement, a huge Communist-led demonstration, and brought Kang into close contact with Party leaders

Liu Shaoqi,

Li Lisan and

Zhang Guotao.

[12] Kang participated in the March 1927 worker's insurrection alongside

Gu Shunzhang and under the leadership of

Zhao Shiyan, Luo Yinong, Wang Shouhua and

Zhou Enlai.

[13] When the uprising was put down by the

Kuomintang with the crucial assistance of

Du Yuesheng's

Green Gang in the

Shanghai massacre of April 12, 1927,

[14] Kang was able to escape into hiding.

[15]

Also in 1927, Kang married a

Shanghai University student and fellow

Shandong native, Cao Yi'ou (born Cao Shuqing), who was to become a lifelong political ally.

[16] He entered the employment of Yu Qiaqing, a wealthy businessman with strong

Kuomintangsympathies, as Yu's personal secretary.

[17] At the same time, Kang remained an active but secret Party organizer, and was named to the Party's new

Jiangsu Provincial Committee in June 1927.

[18]

In the late 1920s, Kang worked closely with

Li Lisan,

[19] a favorite of the

Comintern, who had been made head of the Propaganda Department at the CPC's Sixth Congress, which for security reasons and proximity to the Comintern's congress was held outside Moscow in mid-1928.

[20] Several months after the Sixth Congress, Kang was named director of the Organization Department of the Jiangsu Provincial Committee, which controlled personnel matters.

[21]

In 1930, while in Shanghai, Kang was arrested along with several other Communists, including Ding Jishi, and later released. Ding's uncle Ding Weifen, who was head of the

Kuomintang Central Party School in

Nanjing, where he worked with

Chen Lifu, head of the Kuomintang's secret service.

[22] Kang later denied he had ever been arrested, as the circumstances of his release suggested that he had, as Lu Futan alleged in 1933, "sold out his comrades" in order to secure his freedom. As Byron and Pack note, however, "Kang's arrest in itself is no proof that he was turned by his captors or forced into long-term cooperation with them. KMT [Kuomintang] prisons were notoriously chaotic and corrupt."

[23]

After Li Lisan's adventurism and the failed

Changsha operation of June 1930 lost Li the support of the Party, Kang moved adroitly to align himself with the Comintern's new favorite,

Wang Ming,

[24] and

Pavel Mif's young students from

Sun Yat-sen University, later known as the

28 Bolsheviks, who took control of the Party Politburo at the Fourth Plenum of the Sixth Central Committee on January 13, 1931.

[25] Kang allegedly demonstrated his loyalty to Wang Ming by betraying to the Kuomintang secret police a meeting convened on January 17, 1931 by He Mengxiong, who had been strongly opposed to Li Lisan and was disgruntled by

Pavel Mif's high-handed role in securing the ascendancy of Wang within the Chinese Communist Party.

[26] On the night of February 7, 1931, He Mengxiong and 22 others were executed by the Kuomintang police at Longhua, Shanghai.

[27]Among those murdered were five aspiring writers and poets, including

Hu Yepin, lover of

Ding Ling and father of her child, later canonized as a martyr by the Party.

[28]

The April 1931 arrest and defection to the Kuomintang of

Gu Shunzhang, former

Green Gang gangster and member of the Party's Intelligence Cell, led to serious breaches in Party security and the arrest and execution of

Xiang Zhongfa, the Party's General Secretary.

[29] In response, Zhou Enlai created a Special Work Committee to oversee the Party's intelligence and security operations. Chaired by Zhou personally, the committee included Chen Yun,

Pan Hannian, Guang Huian and Kang Sheng. When Zhou left Shanghai for the Communist base in

Jiangxi Province in August 1931, he left Kang in charge of the Special Work Committee, a position he held for two years. In this role, Kang was "in charge of the entire Communist security and espionage apparatus, not only in Shanghai but throughout KMT China."

[30]

Moscow

In July 1931, Wang Ming removed himself to Moscow and assumed the position of chief Chinese representative on the

Comintern. Kang and his wife Cao Yi'ou followed two years later. Kang remained in Moscow for four years, acting as Wang's deputy on the Comintern, returning to China in 1937.

[31] While in Moscow, Kang was elected a member of the Politburo of the CPC, perhaps as early as 1931

[32] but more probably in January 1934.

[33]

As Byron and Pack put it, "Kang had no cause to regret working with Wang in Moscow. His own prestige and power grew ever greater, and his cocoon of privilege insulated him from the irritations of daily life. But being in Moscow also excluded Kang and

Wang Ming from the drama that was unfolding in China at the time."

[34] That "drama" included the epic retreat of the Communists from Jiangxi Province to

Yan'an, which became known to history as the

Long March, and the ever-growing power within the CPC of

Mao Zedong.

[35] As the French military historian

Jacques Guillermaz observed,

[T]he

Long March helped the Chinese Communist Party to achieve a greater independence of Moscow. Everything tended in the same direction – Mao Zedong's appointment as Chairman of the Party, happening as it did in unusual conditions, practical difficulties in maintaining contact, the

Comintern's tendency to remain in the background to help the creation of popular fronts, under cover of patriotism or ant-fascism. In fact, after the

Zunyi Conference, the Russians seem to have had less and less influence in the Chinese Communist Party's internal affairs. In light of more recent history, this was perhaps one of the major consequences of the Long March.

[36]

Wang Ming's influence over the main Communist forces was minimal after Mao Zedong's emergence from the Zunyi Conference of January 1935 as the undisputed head of the Party. From Moscow, Wang and Kang did seek to maintain control over Communist forces in

Manchuria, which were ordered by them to conserve their strength and avoid direct confrontation with the Japanese army. This directive, which Kang later denied even existed, was resisted by some Manchurian leaders and later criticized by

Mao Zedong as evidence of Wang Ming having stifled Manchuria's revolutionary potential.

[37]

Following the assassination of

Sergei Kirov in December 1934,

Joseph Stalin commenced his great purges of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

[38] Following this example, and with Wang Ming's support, Kang established in 1936 the Office for the Elimination of Counterrevolutionaries and worked closely with the Soviet secret police, the

NKVD, in purging perhaps hundreds of Chinese then in Moscow.

[39] As Byron and Pack put it:

Kang gained great power from the Elimination Office, which he used to silence opponents and witnesses to any embarrassing episodes in his past, especially his arrest in Shanghai. … This was not the first time the Chinese in Moscow had fallen victim to purges. Soviet authorities had made numerous arrests at

Moscow Sun Yat-sen University during the late 1920s; students disappeared into the night, never to be seen again. But Kang worked his own variation: in the past, the Chinese had been purged by the Soviets; now, under Kang, they were liquidated by their fellow Chinese.

[40]

Stalin was more tolerant of the Chinese in Moscow than he was of other foreign Communists, who were purged along with their Soviet comrades. This may have been motivated by a concern about the potential threat of a Japanese invasion of the Soviet Far East. In any case, at this time Stalin began to promote the idea of a united front of the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang against the Japanese, a policy that

Wang Ming and Kang quickly endorsed. In November 1937, following the

Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the Japanese invasion of China, Stalin dispatched Wang and Kang to

Yan'an on a specially provided Soviet plane.

[41]

Kang had played a wily game in the complex and murky world of Stalin's Moscow, earning the following comment from

Josip Broz Tito, who had met Kang in Moscow in 1935:

It can be said without any shadow of a doubt that at that time Kang Sheng was playing a multiple game. On the one hand he was humoring Stalin, but at the same time he was betraying his confidence. Similarly, he had made contact with the

Trotskyists, and had considered joining their movement, but he had also taken steps to infiltrate and sabotage their Fourth International….

[42]

Tito made these comments to

Hua Guofeng on his only visit to China, in 1977 after Kang was dead, and certainly had his own agenda in doing so, but as Faligot and Kauffer remark, "[i]n any case, Tito certainly got the measure of Kang's psychology: a multifaceted game of mirrors was certainly his style, even in the 1930s."

[43]

Yan'an

When Kang Sheng arrived in the Party's redoubt at Yan'an in late November 1937 as part of Wang Ming's entourage, he may have already realized that Wang Ming was falling out of favor, but he initially supported Wang and the Comintern's efforts to guide the Chinese Communists back into line with Soviet policy, especially the need to align with the Kuomintang against the Japanese. Kang also brought Stalin's obsession with Trotskyism to play in helping Wang defeat the efforts of Zhou Enlai and

Dong Biwu to bring

Chen Duxiu back into the Party.

[44]

After assessing the situation on the ground in Yan'an, however, in 1938 Kang decided to re-align himself with Mao Zedong. Kang's motives are easy to imagine. For Mao's part, as MacFarquhar put it,

Kang Sheng was a valuable catch for Mao as he strove to consolidate the power he had won at the Zunyi Conference in January 1935. Kang could betray all the secrets of Wang Ming and his supporters. He was au fait with Moscow politics and police methods, and sufficiently fluent in Russian to act as a major contact with Soviet visitors. He had absorbed sufficient

Marxism-Leninism and Stalinist polemicizing to affect the patina of a theorist, and he was a fluent writer.

[45]

At Yan'an, Kang was close to

Jiang Qing, who may have been Kang's mistress when he visited Shandong in 1931.

[46] In Yan'an, Jiang became the lover of Mao Zedong, who later married her. In 1938, Kang earned Mao and Jiang's gratitude by supporting their liaison against the opposition of more socially conservative cadres, who were aware of her past and uncomfortable with it. Byron & Pack assert that

Kang acted decisively to protect Mao and rebut the charges against Jiang Qing. Invoking his background as head of the Organization Department and as an expert on security and espionage matters, Kang vouched for Jiang Qing. She was a Party member in good standing, he declared, and had no affiliations that would bar marriage to Mao. Kang's personal knowledge of Jiang Qing's past was fragmentary and certainly insufficient to allow him to prove that she was not a KMT agent, but he doctored her record, destroyed adverse material, discouraged hostile witnesses, and coached her on how to answer the probing questions of high-level interrogators who hoped to discredit Mao.

[47]

This episode is believed by many to have been key to Kang's future success, which depended not only on his considerable talents but also on his relationship with Mao. In addition to politics, Kang and Mao also shared an interest in classical culture, including poetry, painting and calligraphy.

[48]

Mao's relationship with Kang, in Yan'an and later, was mainly based on political calculation. Kang's familiarity with Wang Ming enabled him to provide Mao with valuable information about Wang's subservience to the Soviets. Although cadres such as Chen Yun, who had been in Moscow with Wang and Kang, were aware of Kang's previous slavish support for Wang, Kang strenuously sought to change that history and obscure previous affiliations.

[49]

In addition, Mao, who in these years had not yet visited the

Soviet Union, used Kang during this period as a valuable source of information about Soviet affairs. Mao was also suspicious of the Russians and, soon after aligning himself with Mao, Kang also began to speak out against the Soviet Union and its agents in China.

Pyotr Vladimirov, the

Comintern agent sent to Yan'an, recorded that Kang kept him under constant surveillance and even forced

Wang Ming to avoid meeting him.

[50] Vladimirov also believed that Kang delivered biased reports of Soviet affairs to Mao.

[51]

When Stalin shifted his support from Wang Ming to Mao Zedong, the Personnel Department of the Executive Committee of the

Comintern (the "ECCI") included Kang's name on a list of CPC cadres who should not be included in the leadership.

[52]According to Pantsov & Levine,

Once again, the ECCI and, standing behind it, Stalin himself, helped Mao to consolidate his power. This time they even overdid it. Mao did not view Kang Sheng, who had already openly switched to his side, nor several of these other party officials [named in the ECCI Personnel Department memorandum] as his foes. He even tried to defend Kang Sheng in one of his letters to [Georgii] Dimitrov. "Kon Sin [Kang Sheng]," Mao wrote, "is reliable."

[53]

While in Yan'an, Kang oversaw intelligence operations against the Party's two principal enemies, the Japanese and the Kuomintang, as well as potential opponents of Mao within the Party. Chang and Halliday write that "

Shi Zhe observed that Kang was living in a state of deep fear of Mao in this period" because of his murky past, which had been raised with Mao in many letters from cadres and by the Russians, yet "[f]ar from being put off by Kang's murky past, Mao positively relished it. Like Stalin, who employed ex-

Mensheviks like

Vyshinsky, Mao used people's vulnerability as a way of giving himself hold over subordinates."

[54] Vladimirov believed that Kang was behind, at Mao's behest, the attempt by

Li Fuchun and Jin Maoyao to murder Wang Ming by means of mercury poisoning,

[55] although this claim remains controversial.

China's wartime existential crisis provided a perfect excuse for the rival, yet parallel, states [in Chongqing, Nanjing and Yan'an] to use similar techniques, from blackmail to bombing, to achieve their ends, and mute the criticisms of their opponents. If each of them paid tribute to

Sun Yat-sen in public, they also each paid court to the thinking and techniques of Stalin in private.

[57]

In the person of Kang Sheng, Mao had at his disposal a man "trained by one of the world's greatest experts in the abuse of human bodies and minds: the head of the Soviet

NKVD,

Nikolai Yezhov"

[58] As Mitter explains,

Kang Sheng was the mastermind behind the "pain and friction" that underlay the Rectification process. He used a classic Soviet technique of accusing loyal party members of being Nationalist spies. Once they had confessed under torture, their confessions could then set off an avalanche of accusations and arrests. As the war worsened in 1943, and the Communist area become more isolated, Kang stepped up the speed and ferocity of the purges.

[59]

Kang was sufficiently brutal in his methods to arouse the opposition of senior cadres, including

Zhou Enlai,

Nie Rongzhen and

Ye Jianying. At the same time, Mao was not keen to have a single man in such a position of power. Accordingly, following the CPC's Seventh Congress in April 1945, Kang was replaced as head of both the Social Affairs Department and the Military Intelligence Department.

Byron and Pack write that "In spite of Kang's decline, his influence on the security and intelligence system was visible for decades to come. The methods he popularized in Yan'an shaped public security work through the

Cultural Revolution and beyond."

[60] Moreover,

[f]or many victims of Rectification, release and rehabilitation in 1945 after the Seventh Party Congress did not protect them permanently against Kang. During the

Cultural Revolution, he searched many of them out, arrested them and charged them again with being traitors or renegades. A standard item of evidence used against them was a record of their arrest in Yan'an during the Rectification Movement – phony charges from the 1940s appeared twenty years later as "proof" of an individual's disloyalty.

[61]

From Yan'an to the Cultural Revolution

After his fall from the security posts, in December 1946 Kang was assigned by Mao,

Zhu De and

Liu Shaoqi to review the Party's land reform project in Longdong,

Gansu Province. He returned after five weeks with the view that land reform needed to be more severe and that there could be no compromise with landlords. "Kang whipped up hatred for the landlords and their retainers. In the name of social justice, he encouraged the peasants to settle scores by killing landlords and rich peasants."

[62]

In March 1947, Kang put his methods into practice in Lin County,

Shanxi Province. These methods included special scrutiny and persecution of landlords known to have Communist sympathies and investigation of the backgrounds of the Party's land reform teams themselves. In April 1948, Mao singled out Kang for praise in his handling of land reform, with the result that

[A]grarian reform cut a bloody swath through much of rural China. Squads of Communist enforcers were sent to the most remote villages to organize the local petty thieves and bandits into so-called land reform teams, which inflamed the poor peasants and hired laborers against the rich. When resentment reached fever pitch, peasants at staged "grievance meetings" were encouraged to relate the injustices and insults they had suffered, both real and imagined, at the hands of "the landlord bullies." Often these meetings would end with the masses, led by the land reform teams, shouting "Shoot him! Shoot him!" or "Kill! Kill! Kill!" The cadre in charge of proceedings would rule that the landlords had committed serious crimes, sentence them to death, and order that they be taken away and eliminated immediately.

[63]

In November 1947, the CPC Politburo assigned Kang to inspect land reform in his home province of

Shandong. Early in 1948, he was appointed deputy chief of the Party's East China Bureau, under

Rao Shushi.

[64] Some commentators speculate that the private humiliation of being placed under a former subordinate may be one reason why Kang "fell ill" and largely disappeared from view until after Rao's fall in 1954.

[65] Of course, Kang may really have been ill. Mao's personal physician,

Li Zhisui, later recorded that doctors responsible for Kang's treatment at Beijing Hospital told him that Kang was suffering from

schizophrenia.

[66] Writing before Li's book was published, Byron and Pack offered other possible diagnoses based on symptoms Kang seems to have displayed, including manic-depressive psychosis and temporal lobe epilepsy.

[67]

Kang's re-emergence on the political stage in the mid-1950s occurred at roughly at the same time as the

Gao Gang-

Rao ShushiAffair and the affair of Yu Bingbo.

[68] Faligot and Kauffer see these affairs as each showing signs of involvement by Kang Sheng, who they believe used them as means to return to power.

[69]

The challenges that Kang faced during the early months of 1956 underscored the dangers he would have risked by continuing his retreat. As soon as he reappeared, Kang encountered serious problems that caused his position in the hierarchy to fluctuate dramatically. After the purge of

Gao Gang and

Rao Shushi in 1954, he had ranked sixth, below Chairman Mao,

Liu Shaoqi,

Zhou Enlai,

Zhu De and

Chen Yun. But in February 1956, just weeks after his return to public life, he was listed below

Peng Zhen. By the end of April he was reported in tenth place, even below

Luo Fu, the only member of the

28 Bolsheviks who still held a Politburo seat. Yet on

May Day of 1956 – the international socialist celebration – Kang was suddenly back in sixth place. His position, at least going by public reports and official bulletins, remained unchanged from then until the Eighth Congress four months later.

[70]

Kang suffered a severe reversal of fortune at the Central Committee plenum that followed the first session of the CPC's Eighth Congress, when he was demoted to alternate, nonvoting membership of the Politburo. Roderick MacFarquar writes

The reasons for Kang Sheng's reduction to alternate membership of the Politburo are not clear. …[T]he immediate reason for his demotion may have been the general revulsion against secret police within the communist bloc after Khrushchev's

Secret Speech.

[71] Kang Sheng's emergence during the cultural revolution as one of the most important Maoist stalwarts suggests that…it is not unlikely that at the 8th Congress Mao saved Kang from even greater humiliation.

[72]

Mao's own position was weakening, as evidenced by the decision of the CPC's Eighth Congress to delete the phrase "guided by the thought of Mao Zedong" from the new Party constitution and by re-establishing the role of General Secretary, abolished in 1937.

[73] The dangers of exalting a single leader and the desirability of collective leadership had been perhaps the most direct point of

Nikita Khrushchev's

Secret Speech to the Twentieth Congress of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union (the "CPSU") in February 1956, in which he condemned Stalin, Stalin's methods and his cult of personality and which, according to Archie Brown, "was the beginning of the end of international Communism."

[74]

While Kang remained a member of the Politburo, he had no concrete role and no power base, which led him to take on a series of diverse assignments and to align himself as closely as possible with Mao, who was devising his response to de-Stalinization and its effects within the leadership of the CPC.

[75] His responses, in the

Hundred Flowers and the

Anti-Rightist Campaign that followed, marked a profound turning point in the history of the People's Republic of China. As

Maurice Meisner wrote

The period of the

Hundred Flowers was the time when the Chinese abandoned the Soviet model of development and embarked on a distinctively Chinese road to socialism. It was the time that China announced its ideological and social autonomy from the

Soviet Union and its

Stalinist heritage. It is a cruel and tragic irony that the break with the Stalinist pattern of socioeconomic development was not accompanied by a break with Stalinist methods in political and intellectual life. The latter was precluded by the suppression of the critics who had briefly "bloomed and contended" in May and June 1957.

[76]

As noted in connection with the

Yan'an Rectification Movement launched 15 years earlier, Kang Sheng played an important role in bringing Stalinist methods of repression to China.

[77]

Kang was clearly a supporter of Mao during the period of the

Great Leap Forward and its aftermath and, as MacFarquar writes, "[h]e was the beneficiary of Mao's practice of preserving and protecting those whom he trusted and relied upon, and for whom he saw a future use."

[78] As a result, Kang received a number of important positions during the late 1950s, including in 1959 responsibility for the Central Party School.

[79]

Among Kang's most important activities in this period were those related to the deepening split with the

Soviet Union, about which Mao and others regarded him as something of an expert. Among his assignments from the Politburo was to draft a long article that appeared in

The People's Daily on December 29, 1956 under the title "More on the Historical Experience of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat" and which expressed the Party's position that Stalin's achievements overshadowed his mistakes.

[80]

Kang visited the Soviet Union and various socialist countries in Eastern Europe on several occasions between 1956 and 1964, expressing increasing disdain for the "revisionist" policies of

Nikita Khrushchev and

Josip Broz Tito.

[81] In February 1960, as the Chinese observer at the conference of the Political Consultative Conference of the

Warsaw Pact, Kang made what Jacques Guillermaz described as "a violent attack on the leaders of the United States, their feigned pacifism, their dream of 'peaceful evolution' of the socialist countries, and their repeated sabotage of disarmament."

[82] Byron and Pack describe the speech as "a subtle, almost sarcastic critique of Russian foreign policy that became a milestone in deteriorating Sino-Soviet relations."

[83]

The following year, Kang was one of the Chinese delegates to the Twenty-Second Congress of the CPSU to leave their seats to avoid shaking hands with Khrushchev.

[84] Kang was also a member of the delegation that attended a meeting in Moscow in July 1963, which failed to bridge the growing gap between the Chinese and Soviet parties. Among the points of contention, raised in a letter issued by the Chinese Communist Party on June 14, 1963, had to do with de-Stalinization and the allegation that

[u]nder the pretext of "combating the cult of the individual," certain persons are crudely interfering in the internal affairs of other fraternal parties and fraternal countries and forcing other fraternal parties to change their leadership in order to impose their own wrong line on those parties.

[85]

Jacques Guillermaz asked rhetorically of this criticism, "[c]ould the Chinese really have been thinking of

Enver Hoxha?"

[86]

The Sino-Soviet rift and the obsession with Khruschev's revisionism looms large in the coming of the Cultural Revolution, as Mao saw revisionism and de-Stalinization as a threat not only to his own position but also to the very survival of the Chinese Communist Party as a revolutionary force.

[87] Accordingly, an appreciation Kang's role as a supporter of Mao's line in this period helps explain his return to very near the pinnacle of power a few years later.

Cultural Revolution

As an important ally of

Mao Zedong's efforts to regain control of the CPC, Kang was an important enabler of and participant in the Cultural Revolution, later described by the CPC's Central Committee as having "lasted from May 1966 to October 1976" and as "responsible for the most severe setback and heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the state and the people since the founding of the People's Republic." The Central Committee resolution concluded that the Cultural Revolution "was initiated and led by Comrade Mao Zedong."

[88] In outlining the "errors" that had been made by Mao and others in the run-up to the

Cultural Revolution, the Central Committee noted that "[c]areerists like

Lin Biao,

Jiang Qing and Kang Sheng, harbouring ulterior motives, made use of these errors and inflated them."

[89]

Well before the start of the Cultural Revolution as such, Kang played his part in attacking rivals of Mao in the Party leadership, many of whom were unhappy with a range of policies including Mao's refusal to rehabilitate

Peng Dehuai, the former Defense Minister and outspoken critic of the

Great Leap Forward. In 1962, Kang used the publication of a novel about

Liu Zhidan, a Party member killed in battle against the

Kuomintang in 1936, as the basis for reviving the

Gao Gang affair, successfully insinuating that the novels' publication was an effort by

Xi Zhongxun and others to reverse the Party's verdict on Gao.

[90] As a result of this, Kang was promoted to the secretariat of the Central Committee at the 10th Plenum in August 1962. As MacFarquar writes,

Two months later, [Kang] moved to the

Diaoyutai guest complex in the capital to mastermind a team of ideologues for the campaign against Soviet revisionism. The most cynical hit-man of Mao's Cultural Revolution swat team was now an agent in place, helping to initiate the domestic and foreign policies that were the prelude to that cataclysm.

[91]

In January 1965, Mao suggested to the Party Politburo that the principal enemies of socialism in China were "those people in authority within the Party who are taking the capitalist road" and urged that the Party undertake a "cultural revolution."

[92] The Politburo established a five-man group, chaired by

Peng Zhen, its fifth-ranking member and head of the Beijing Party Organization and mayor of the capital city. Kang Sheng was named a member of the group, which remained dormant for most of the year.

[93]

In early 1965, Mao sent his wife

Jiang Qing to Shanghai to light the first spark of what would become the Cultural Revolution, the campaign against

Wu Han, the Vice Mayor of Beijing and the author of the 1961 play

Hai Rui Dismissed from Office. The attack on Wu Han was an indirect attack on Beijing's mayor,

Peng Zhen, a pillar of the establishment that Mao wanted overthrown. Kang's role in the subsequent purge of Peng was to co-lead with

Chen Boda the prosecution of Mao's charge that "

Peng Zhen, the Propaganda Department, and the Beijing Party Committee had shielded bad people while suppressing leftists."

[94] Following the purge of

Peng Zhen in May 1966, the Central Committee later concluded, "

Lin Biao,

Jiang Qing, Kang Sheng,

Zhang Chunqiao and others…exploited the situation to incite people to 'overthrow everything and wage full-scale civil war.'"

[95]

In May 1966, Kang Sheng sent his wife, Cao Yi'ou, to

Beijing University as part of a team designed to rally leftists against the university president,

Lu Ping, and other officials aligned with Peng Zhen.

[96] Cao sought out

Nie Yuanzi,

[97] a Party branch secretary in the Philosophy Department with whom Kang and Cao had become acquainted years earlier in Yan'an.

[98] With information from Cao Yi'ou that Lu Ping had lost high-level Party protection,

Nie Yuanzi and her leftist allies launched a movement that over the next three months threw Beijing University into chaos. As Yue Daiyun wrote:

With no limits imposed, no guidance offered, no one assuming responsibility for what occurred, and the

Red Guards merely following their impulses, the assault upon their elders and the destruction of property grew completely out of control.

[99]

During the Cultural Revolution, Kang Sheng was actively involved in controlling the CPC propaganda apparatus, being appointed head of the "

Central Organization and Propaganda Leading Group",

[100] while

Yao Wenyuan as head of another "Propaganda Leading Group". In November 1970, Kang was elevated to head of the Propaganda Department.

In 1968, Mao and other leaders finally began to rein in the

Red Guards, with Kang Sheng playing a leading role. In January Kang denounced the

Hunan shengwulian coalition of Red Guards as "

anarchists" and "

Trotskyists," launching a campaign of brutal suppression over the following months by the army and secret police.

[101] By July, when Mao joked that with a group of Red Guard leaders that he himself was the "black hand" suppressing campus revolutionaries, the glory days of the movement were ending.

[102]

In the turbulent years of the Cultural Revolution, Kang remained close to the pinnacle of power and, as the "evil genius" within the Central Case Examination Group (the "CCEG") established by the CPC Politburo on May 24, 1966, was instrumental in Mao's efforts to purge many senior Party officials, including his most senior rival within the Party,

Liu Shaoqi.

[103] In the subsequent trial of the so-called "

Gang of Four," one of the accusations leveled against

Jiang Qing was that she conspired "with Kang Sheng,

Chen Boda, and others to take it upon themselves to convene the big meeting [on July 18, 1967] to apply struggle-and-criticism to Liu Shaoqi, and to carry out a search of his house, physically persecuting the Head of State of the People's Republic of China."

[104] Xiao Meng testified at the trial that "the slander and persecution of [Liu Shaoqi's wife]

Wang Guangmeiwas plotted by Jiang Qing and Kang Sheng in person."

[105]

Kang's position on the CCEG gave him enormous, if invisible power. The very existence of the CCEG remained a secret, "[y]et," as MacFarquar and Schoenhals write,

During its thirteen-year existence, the CCEG had powers far exceeding not only those once exercised by the Party's Discipline Inspection Commission and Organization Department, but even those of the central public security and procuratorial organs and the courts. The CCEG made the decision to "ferret out," persecute, arrest, imprison and torture "revisionist" [Central Committee] members and many lesser political enemies. Its privileged employees were the Cultural Revolution equivalent of

Vladimir Lenin's

Cheka and

Adolf Hitler's

Gestapo. Whereas the [Central Cultural Revolution Group] at least nominally dealt in "culture," the CCEG dealt exclusively in violence.

[106] The CCEG was established as an

ad hoc body but soon became a permanent institution with a staff of thousands that, at one point, was investigating no fewer than 88 members and alternate members of the Party Central Committee for suspected "treachery," "spying," and/or "collusion with the enemy."

[107]

During the Cultural Revolution, Kang abused his position to personal advantage. A gifted painter and calligrapher,

[108] he used his power to indulge his penchant for collecting antiques and works of art, notably inkstones. According to Byron & Pack, many of the

Cultural Revolution leaders also used the lawlessness of the period to acquire for themselves objects seized from the homes of persons attacked by Red Guards. But Kang, in a series of visits to the Cultural Relics Bureau, "helped himself to 12,080 volumes of rare books – more than were taken by any other radical leader, and 34 percent of all the rare books removed – and 1,102 antiques, 20 percent of the total. Only

Lin Biao, who, as Mao's designated heir, ranked second in the land, appropriated more antiques than Kang."

[109]

Kang Sheng was instrumental in supervising the drafting of the new Party Constitution, adopted at the CPC's Ninth Congress in April 1969, which reinstated "

Mao Zedong Thought" alongside

Marxism-Leninism as the theoretical basis for the Party. The Congress elected Kang as one of the five members of the Politburo Standing Committee, along with Mao, Lin Biao, Zhou Enlai and

Chen Boda.

[110] At the Ninth Congress, Kang Sheng's wife, Cao Yi'ou, was herself elected to the Central Committee.

[111]

The Constitution drafted under Kang's supervision and adopted at the Ninth Congress stipulated that "Comrade Lin Biao is Comrade Mao Zedong's close comrade-in-arms and successor."

[112] Kang Sheng and Lin Biao were not close allies, although Kang had earlier assisted Lin in his successful efforts to remove Marshal

He Long, a formidable rival to Lin's wish to control the

People's Liberation Army.

[113] In the wake of Lin Biao's aborted coup attempt and death in September 1971, Kang was careful to distance himself from Mao's disgraced former heir and from

Chen Boda, who had been closely aligned with Lin at the Central Committee meeting in Lushan in August 1970 and who was denounced after Lin's fall at "China's Trotsky."

[114] Efforts to link Kang to Lin Biao's plotting were unsuccessful and unsubstantiated.

[115]

Ill with the cancer that would eventually kill him, Kang last appeared in public at the Tenth Congress of the CPC, in August 1973. The Tenth Congress adopted a new Constitution that removed the embarrassing reference to Lin Biao as Mao Zedong's successor, but as a sign that his position had not been adversely affected, Kang Sheng was named one of five vice chairmen of the Party.

[116] In his final years, Kang became involved in the

Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius campaign that was created by the beneficiaries of the Cultural Revolution to oppose

Zhou Enlai and other veteran officials in the struggle over who would succeed

Mao Zedong. Kang was initially active in supporting

Jiang Qing, perhaps seeing her as a successor through whom he would exercise power.

[117] Kang subsequently shifted tack when it became apparent that Jiang was out of favor with Mao, even going so far as to denounce her as having betrayed the Party to the

Kuomintang during the mid-1930s, notwithstanding his support for her when the same charge had been leveled 30 years earlier in Yan'an.

[118] Kang's final political act came only two months before his death, when he warned Mao Zedong that

Deng Xiaoping opposed the Cultural Revolution and should be purged again, advice that Mao ignored.

[119]

Support for the Khmer Rouge

Kang also left a lasting imprint on China's foreign policy. As MacFarquhar writes, "[t]he dual role of Kang Sheng in Mao's campaign against revisionism at home and abroad symbolized the close relationship between Chinese domestic and foreign policy."

[120] Kang's contribution to the dispute with the

Soviet Union about de-Stalinization has been described above in connection with the his efforts to insinuate himself with Mao and developing the ideological origins of the Cultural Revolution.

Perhaps Kang's most important influence over Chinese foreign policy came during the Cultural Revolution itself, when he was instrumental in developing Chinese support for the

Khmer Rouge regime in

Cambodia. While the mainstream of the CPC leadership supported Prince

Norodom Sihanouk as Cambodia's anti-Western and anti-imperialist leader, Kang argued that Khmer Rouge guerrilla leader

Pol Pot was the real revolutionary leader in the Southeast Asian nation.

Kang's backing of Pol Pot was an effort to back his own cause within the CPC, as his touting of Pol Pot as the true voice of the Cambodian revolution was in large part an attack on the Chinese Foreign Ministry, whose pragmatic support for Prince Sihanouk's regime was thereby presented as reactionary. As a result of his success in this, the Pol Pot regime came to power and the Khmer Rouge became the recipient of Chinese aid for years to come, prolonging the life of that movement with tragic consequences for Cambodia.

[121]

Death and disgrace

Kang Sheng died of bladder cancer on December 16, 1975. He was given a formal funeral, attended by every member of the Politiburo except Mao, who did not attend funerals at this stage, and

Zhou Enlai and

Zhu De, who both were too weak to attend. Marshal

Ye Jianying delivered a eulogy in which he praised Kang as "a proletarian revolutionary, a

Marxist theoretician, and a glorious fighter against revisionism."

[122]

In November 1978,

Hu Yaobang voiced the first formal criticism of Kang in a speech to the Central Party School. Ruan Ming reports Hu as telling four of Kang's "anti-revisionist scribblers" that

you four people have played an extremely negative role in the liberation of thought, the role of a brake. As far as I'm concerned, this is because you have come too much under the influence of people like Kang Sheng. … Kang Sheng passed his time reading between the lines looking for "allusions" without taking account of the real subject of articles and the general idea. He made a sort of talent of looking for a particular point he could attack. He had learned this from Stalin, from

Andrei Zhdanov and the

KGB, and acted thus from the time of the Yan'an era.

[123]

As fear of Kang subsided following the arrest of the

Gang of Four and the return to power of

Deng Xiaoping, criticisms of Kang Sheng grew and a special case group was established to investigate Kang's career. In late summer 1980, the special case group reported to the CPC Central Committee. In October 1980, just in advance of commencing the trial of the Gang of Four, Kang Sheng was posthumously expelled from the CPC and the Central Committee formally rescinded Marshal

Ye Jianying's eulogy.

[124]

Những Năm Tháng Khuyết

Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years - 1919 -1941 Sophie Qinn-Judge

0o0

Ban thẩm tra vụ việc NGUYỄN ÁI QUỐC ở Quốc tế Cộng sảnBá Ngọc

Trong quá trình 30 năm đi tìm đường cứu nước, Hồ Chí Minh đã từng ba lần 1923 - 1924, 1927 - 1928, 1934 - 1938 sống ở nước Nga Xô viết. Đặc biệt, giai đoạn 1934 - 1938 đã để lại cho Người những kỷ niệm sâu sắc. Biên niên tiểu sử của Người giai đoạn này vẫn đang còn là khoảng trống. Đã có lúc Người phải giãi bày về hoàn cảnh của mình : “ Trong hoàn cảnh không hoạt động gì ”, “ đứng ngoài Đảng ”... Nhưng, đây là thời kỳ độc đáo của một chân dung chính trị, ẩn mình trong nhiều vấn đề nhạy cảm, thể hiện nổi bật bản lĩnh chính trị Hồ Chí Minh.

Tâm điểm chú ý nhất của giai đoạn này là việc thành lập Ban thẩm tra vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc ở Quốc tế Cộng sản. Đây được xem là trung tâm thu hút mọi vấn đề liên quan trực tiếp đến cuộc đời, sự nghiệp, vận mệnh chính trị của Nguyễn Ái Quốc.

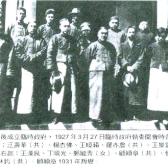

Ban chấp hành Quốc tế Cộng sản 1935

Từ trái sang phải, hàng ngồi : André Marty, G.Dimitrov, Palmiro Togliatti, V. Florin, Vương Minh ;

hàng đứng : M. Moskvin, Otto Kuusinen, Klement Gottwald, Wilhelm Pieck, Dmitry Manuilsky.

Ban thẩm tra vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc ở Quốc tế Cộng sản được thành lập tháng 2 năm 1936, trong một giai đoạn

lịch sử phức tạp, căng thẳng. Đại chiến thế giới lần thứ 2 đang đến gần, các nước tư bản thù địch bao vây quyết tiêu diệt chính quyền Xô viết ở nước Nga, nội bộ Quốc tế Cộng sản do nhiều lý do khách quan và chủ quan gặp rất nhiều khó khăn, thử thách. Trong bối cảnh lịch sử đó, Đảng Cộng sản Đông Dương phải trải qua những ảnh hưởng khác nhau về quan điểm tư tưởng và đường lối cách mạng Việt Nam. Tình hình chung ít nhiều ảnh hưởng trực tiếp đến từng người cụ thể, đến từng vụ việc cụ thể, nếu như người đó trước đây và hiện tại có “ vấn đề ” về chính trị hoặc vướng mắc về mặt nào đó liên quan đến tổ chức.

Nguyễn Ái Quốc lúc này đang là học viên Trường Đại học Phương Đông, nhưng lại là tâm điểm chú ý của dư luận trong nội bộ Quốc tế Cộng sản và Đảng Cộng sản Đông Dương, bởi “ nghi án ” của những vụ việc trước đây như sự kiện thành lập Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam với tên gọi và chính cương, sách lược vắn tắt tập hợp địa chủ và tư sản dân tộc là động lực của cách mạng giải phóng dân tộc. Tuy rằng đến ngày nay, đó vẫn là sự sáng suốt và đúng đắn của lãnh tụ Hồ Chí Minh, nhưng thời kỳ đó cho rằng là sai lầm, hữu khuynh, dân tộc chủ nghĩa, tư tưởng tiểu tư sản...

Một loạt dấu hỏi về vụ án Hương Cảng : vì sao chịu án phạt nhẹ, bằng con đường nào để đến được Liên Xô... Đặc biệt bức thư của Ban lãnh đạo Hải ngoại Đảng Cộng sản Đông Dương viết ngày 20/4/1935 (1) gửi Quốc tế Cộng sản cung cấp những thông tin cực kỳ nguy hiểm về Nguyễn Ái Quốc. Nội dung thư kết tội Nguyễn Ái Quốc phải chịu trách nhiệm chính về việc hơn 100 Đảng viên của Đảng Cách mạng Thanh niên bị bắt do việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc biết Lâm Đức Thụ trước đây là kẻ phản bội mà vẫn tiếp tục sử dụng ; Nguyễn Ái Quốc rất sai lầm khi yêu cầu mỗi học viên cung cấp hai ảnh, họ tên, địa chỉ, họ tên cha mẹ, ông bà nói chung những người sinh thành và địa chỉ chính xác của 2 đến 10 bạn thân. Những bức ảnh của các học viên do Nguyễn Ái Quốc và Lâm Đức Thụ yêu cầu đều vào tay mật thám. Ở trong nước, ở Xiêm, ở khắp các nhà tù người ta nói nhiều về trách nhiệm của Nguyễn Ái Quốc. Đường lối chính trị của Đảng Cộng sản do Nguyễn Ái Quốc chỉ đạo trước đây bị phê phán gay gắt trong các Đảng viên và quần chúng cách mạng. Đồng chí Tổng bí thư Đảng Cộng sản Xiêm – người học trò trung thành của Nguyễn Ái Quốc, một trong nhiều người nói rằng, trước năm 1930 Nguyễn Ái Quốc chưa phải là Đảng viên Đảng Cộng sản. Trong thư còn nói về sai lầm của Nguyễn Ái Quốc khi hợp nhất các tổ chức cộng sản vào năm 1930, yêu cầu Nguyễn Ái Quốc trong thời gian gần nhất cần viết cuốn sách tự chỉ trích những sai lầm về chính trị của mình.

Vera Vasilievna

Có phải do bức thư của Ban lãnh đạo Hải ngoại là nguyên nhân chính dẫn đến việc thành lập Ban thẩm tra vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc, hay đó chỉ là “ giọt nước làm tràn ly ”, là cái cớ để những dị nghị âm ỷ lâu nay bùng phát ?

Sau khi tiếp nhận được bức thư của Ban lãnh đạo Hải ngoại, đồng chí Vaxiliepna – người trực tiếp phụ trách Đông Dương của Quốc tế Cộng sản – đã viết bản Báo cáo đề ngày 29-6-1935 (2) dài 3 trang gửi Bộ Phương Đông và Vụ Tổ chức cán bộ của Quốc tế Cộng sản : “ Đề nghị cần nghiên cứu kỹ nội dung bức thư của Ban lãnh đạo Hải ngoại và cung cấp thêm những thông tin về Nguyễn Ái Quốc để Quốc tế Cộng sản có cơ sở đánh giá chính xác, đầy đủ, toàn diện về Nguyễn Ái Quốc ”. Đồng chí Vaxiliepna khẳng định :

“ Nguyễn Ái Quốc là người cộng sản Đông Dương đầu tiên, là người rất có uy tín giữa những người cộng sản, là người đã tổ chức các nhóm cộng sản đầu tiên trên cơ sở đó để thành lập Đảng Cộng sản Đông Dương. Khi hợp nhất Đảng, Nguyễn Ái Quốc tự nhận mình là đại diện của Quốc tế Cộng sản, mặc dầu Quốc tế Cộng sản chưa trao ủy quyền. Trong thời gian hợp nhất Đảng, Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã thành lập Ủy ban lâm thời và đã để xảy ra một số sai lầm như hợp nhất một cách máy móc các nhóm cộng sản, không phân định rõ ràng quan hệ với các tầng lớp địa chủ và tư sản... Do đó, uy tín của đồng chí bị giảm sút, đặc biệt, trong đội ngũ những người lãnh đạo của Đảng Cộng sản Đông Dương. Hội nghị tháng 10-1930 của Đảng Cộng sản Đông Dương đã nghiêm khắc phê phán những khuyết điểm của đồng chí. Sau Hội nghị, Nguyễn Ái Quốc đảm nhận công việc liên lạc viên, công tác tại Trung Quốc và Hồng Kông. Trong các bức thư từ Ban lãnh đạo Đảng phản ánh tâm trạng không bằng lòng của Nguyễn Ái Quốc, về công việc của một liên lạc viên bình thường mà luôn thể hiện vai trò lãnh đạo; đã đưa ra những ý kiến, ghi chú, nhận xét của mình trong các chỉ thị, thông báo của Quốc tế Cộng sản và cản trở những thông tin từ đất nước gửi Quốc tế Cộng sản.

“ Ngày 6-6-1931, Nguyễn Ái Quốc bị mật thám Anh bắt tại Hồng Công và bị kết án 2 năm tù giam. Trong thời kỳ này, chúng tôi(Vaxiliepna) liên hệ với luật sư bào chữa thông qua Tổ chức cứu trợ những người cộng sản bị nạn của Pháp, gửi tiền để thuê luật sư bào chữa và luật sư đã tổ chức cho Nguyễn trốn thoát, việc này đã được luật sư nói rõ trong thư gửi chúng tôi. Một thời gian sau đó, có tin là Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã chết trong tù vì lao phổi. Năm 1933, xuất hiện tin rằng Nguyễn Ái Quốc không chết mà được thả tự do và biến mất.

“ Vào tháng 7-1934, Nguyễn Ái Quốc đến Matxcơva. Theo lời kể của Nguyễn Ái Quốc thì khó xác định được vì sao trốn thoát khỏi mật thám Pháp một cách dễ dàng sau án ngồi tù của mình, và vì sao chỉ bị kết án một cách nhẹ nhàng vậy. Tôi đã nhiều lần đề nghị Nguyễn Ái Quốc trình bày bằng văn bản về các việc liên quan đến bị bắt, bị kết án tù, được giải thoát và trở về với chúng ta, nhưng Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã không thực hiện. Chuyến trở về, theo Nguyễn Ái Quốc kể thì do Vaillant-Couturier trong thời gian ở Trung Quốc đã tổ chức giúp đỡ. Tôi nghĩ rằng, tất cả những vấn đề này cần được thẩm tra kỹ lưỡng. Sau khi đến đây, Nguyễn Ái Quốc được cử đi học tại Trường Mác - Lênin cho đến ngày nay. Thống nhất với các đồng chí Mip và Côchenxky chưa thể nắm hết các hoạt động của Nguyễn Ái Quốc, mặc dầu chúng tôi biết rằng, Nguyễn luôn luôn kiên trì phấn đấu. Nguyễn đã nhiều lần yêu cầu tôi trao đổi về việc tổ chức liên hệ với Đảng, đặc biệt, rất quan tâm tới các chuyến đi công tác của các sinh viên, về việc họ đi đâu và với những nhiệm vụ gì. Nguyễn rất khổ tâm và nóng lòng về việc không được tham gia những nhiệm vụ bí mật. Trong mối quan hệ với các sinh viên, Nguyễn luôn cố gắng đóng vai trò là người thầy, người lãnh đạo, nhưng về lý luận tỏ ra yếu kém và thường xuyên để xảy ra sai sót trong quá trình trao đổi. Trong bản thân Nguyễn chứa đựng nhiều tư tưởng dân tộc chủ nghĩa và tàn dư cũ, những thứ đó có thể chống lại ý nguyện của mình.

Trên đây là những dẫn chứng tôi đã trình bày. Nguyễn Ái Quốc khi tự phê bình tỏ ra bình tĩnh và luôn luôn chấp nhận những tự chỉ trích đó.

Điểm lại những sự kiện và tư liệu, phải chăng cần khẳng định vị trí đại diện trong Đảng của Nguyễn Ái Quốc. Phải chăng Nguyễn Ái Quốc có thể tham gia Đại hội (Quốc tế Cộng sản) như một đại biểu chính thức ”.

(trích báo cáo của Vaxiliepna)

Bản báo cáo của Vaxiliepna được những người có trách nhiệm trong Quốc tế Cộng sản đọc và nghiên cứu kỹ. Xử lý vụ việc như thế nào đây ? Đã có sự trao đổi qua lại giữa Vaxiliepna và các đồng chí trong tổ chức Quốc tế Cộng sản.

Nguyễn Ái Quốc (hàng đầu, thứ 2 từ phải) tham dự Đại hội Quốc tế Cộng sản

(lần thứ 5) tại Moskva năm 1924 cùng Joseph Gothon-Lunion (thứ 3) và Leon Trotsky (thứ 4)

Trong những vụ việc liên quan đến Nguyễn Ái Quốc, những việc nào quan trọng, gây tác động nguy hiểm cần được làm sáng tỏ trước khi Ban thẩm tra thành lập và nhóm họp. Đó là những vụ việc sau :

1. Vì sao biết Lâm Đức Thụ là kẻ phản bội vẫn còn sử dụng ?

2. Vì sao thời gian bị bắt ở Hồng Kông bị tòa án kết tội nhẹ và vì sao thoát tù một cách dễ dàng ?

3. Bằng cách nào để đến được Matxcơva ?

Đồng chí Vaxiliepna đã trực tiếp gặp Nguyễn Ái Quốc trao đổi về những buộc tội có trong thư của Ban lãnh đạo Hải ngoại. Đặc biệt việc vì sao biết Lâm Đức Thụ là kẻ phản bội mà vẫn sử dụng. Nguyễn Ái Quốc trả lời dứt khoát rằng phát hiện Lâm Đức Thụ phản động rất muộn, mãi sau này. Việc này được Tổng bí thư Đảng Cộng sản Đông Dương, đồng chí Hải An (Lê Hồng Phong) đã khẳng định trong báo cáo giải trình về Nguyễn Ái Quốc gửi Quốc tế Cộng sản.

Về việc thời gian bị bắt ở Hồng Kông, vì sao được tòa án kết tội nhẹ và thoát tù một cách dễ dàng, đồng chí Vaxiliepna đã có trong tay chứng cứ thuyết phục rằng đã liên lạc, gửi tiền thuê luật sư Loseby lo việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc thông qua Hội cứu trợ những người cộng sản bị nạn của Pháp.

Bằng cách nào để đến được Matxcơva ? Sau khi ra tù, Nguyễn Ái Quốc bắt liên lạc được với người bạn cũ thời kỳ hoạt động ở Đảng Cộng sản Pháp là Paul Vaillant-Couturier lúc này đang ở Trung Quốc và được bố trí trở lại nước Nga. Quốc tế Cộng sản đã cử đồng chí Radumopva gặp trực tiếp Vaillant-Couturier hỏi về vụ việc và được trả lời là do đồng chí bố trí cho Nguyễn Ái Quốc trở lại nước Nga.

Để chuẩn bị tốt nội dung làm việc cho Ban thẩm tra, Vaxiliepna đã viết Bản giải trình dài 6 trang (3), tổng hợp tất cả những vụ việc liên quan đến quá khứ, hiện tại của Nguyễn Ái Quốc. Đặc biệt, đã đưa ra những ý kiến cực kỳ có lợi cho Nguyễn Ái Quốc, khẳng định rằng Nguyễn Ái Quốc là người Cộng sản chân chính, hy sinh cống hiến hết mình cho Đảng, không phải là kẻ phản bội, chưa bao giờ có sự liên hệ với mật thám. Dẫn đến việc sai lầm về chính trị, chưa có kinh nghiệm hoạt động bí mật, trình độ lý luận còn yếu... là do chưa được đào tạo cơ bản. Gần đây, Nguyễn Ái Quốc tích cực học tập, nghiên cứu, cố gắng vươn lên để nhận thức đúng bản chất những sai lầm trong quá khứ...

Trong Bản giải trình, Vaxiliepna đề nghị thành phần Ban thẩm tra có từ 3 đến 5 người có uy tín lớn, trong đó, dứt khoát phải có mặt của Hải An (Lê Hồng Phong) với Bản giải trình về Nguyễn Ái Quốc. Đây là một đề nghị cực kỳ quý báu, như một sự bảo lãnh vận mệnh chính trị trong sạch của Nguyễn Ái Quốc trước Ban thẩm tra của Quốc tế Cộng sản.

Tháng 2 năm 1936, Ban thẩm tra được thành lập, lúc đầu, có 2 ý kiến bút phê của Lãnh đạo Quốc tế Cộng sản :

Ý kiến một, đề nghị Ban thẩm tra có các đồng chí : 1. Manuinxki. 2. Krapxki. 3. Hải An. 4. Vương Minh. 5. Barixta. 6. Raimốp.

Ý kiến hai, đề nghị gồm các đồng chí : 1. Cônxinna. 2. Hải An. 3. Krapxki. 4. Barixta. 5. Xtipannốp.

Đến ngày 19 tháng 2 năm 1936, do có nhiều lý do khác nhau, thành phần Ban thẩm tra chỉ có các đồng chí: Cônxinna, Hải An và Krapxki.

Ban thẩm tra nhóm họp và đi đến những kết luận chính như sau :

1. Đồng chí Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã mắc một số sai lầm nghiêm trọng trong hoạt động bí mật. Ban thẩm tra yêu cầu đồng chí từ nay không để xảy ra những trường hợp tương tự. Đề nghị đồng chí rút kinh nghiệm bài học này trong hoạt động bí mật sau này.

2. Ban thẩm tra không tìm ra chứng cứ nghi ngờ nào về sự trung thành chính trị của đồng chí Nguyễn Ái Quốc.

3. Hồ sơ vụ việc về Nguyễn Ái Quốc được hủy bỏ.

Bản kết luận đã được Krapxki và Hải An ký.

Sau kết luận của Ban thẩm tra, tưởng chừng vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã được giải quyết xong. Nào ngờ, đến tháng 1 năm 1938, khi Nguyễn Ái Quốc tham gia lớp nghiên cứu sinh Viện nghiên cứu các vấn đề dân tộc và thuộc địa, Ban lãnh đạo Viện đề nghị Vụ Tổ chức cán bộ Quốc tế Cộng sản xác minh việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc ra khỏi tù và vào Liên Xô như thế nào. Trong Thư trả lời Viện Nghiên cứu (4), Vụ Tổ chức cán bộ khẳng định : để giải quyết vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã thành lập Ban thẩm tra và đi đến kết luận về sự trung thành chính trị của Nguyễn Ái Quốc; đồng chí Radumopva đã trực tiếp gặp Vaillant Couturier và được khẳng định chuyến trở về Liên Xô là do Vaillant tổ chức ; hồ sơ vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã được Ban thẩm tra quyết định hủy bỏ. Sau đó, Nguyễn Ái Quốc mới được tiếp nhận làm nghiên cứu sinh Viện nghiên cứu các vấn đề dân tộc và thuộc địa.

Vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc đã lùi xa từ nửa đầu thế kỷ trước, nó như một dấu lặng trong cuộc đời đầy sóng gió của những năm tháng hoạt động ở nước ngoài. Vì nhiều lý do mà đến nay chúng ta chưa tiếp cận được đầy đủ, hoặc chưa xã hội hóa tài liệu lưu trữ thuộc giai đoạn này, do đó, nhận thức về bản chất các sự kiện liên quan đến Nguyễn Ái Quốc gặp nhiều khó khăn.

Nguyễn Ái Quốc tại Đại hội thành lập ĐCS Pháp (1920). Ngồi cạnh (người đầu tiên, từ bên phải) là nhà văn Paul Vaillant-Couturier

Thời kỳ này là thời kỳ khó khăn nhất của Nguyễn Ái Quốc, nhưng với bản lĩnh chính trị vững vàng Người đã vượt qua. Ngoài ra, cần được xem xét những yếu tố khách quan khác. Trong lúc khó khăn nhất, bên cạnh Nguyễn có những người bạn, người đồng chí hết lòng giúp đỡ, như Vaxiliepna, Lê Hồng Phong, Vaillant Couturier, Manuinxki, Radumopva... Thời điểm thành lập Ban thẩm tra (tháng 2 năm 1936) và trước đó chưa rơi vào thời kỳ cao điểm thanh lọc nội bộ Quốc tế Cộng sản, cho nên xem xét vụ việc chưa đến nỗi quá tả ; những người trực tiếp phụ trách phong trào cách mạng Đông Dương hoặc có liên quan đến vụ việc của Nguyễn Ái Quốc chưa bị “ xử lý ” như Vaxiliepna, Krapxki, Radumopva... Với cái cớ rất hợp lý “ do trình độ lý luận yếu ”, Nguyễn Ái Quốc có điều kiện vào trường học suốt thời gian lưu lại ở Liên Xô. Công việc học tập, một mặt nâng cao trình độ lý luận, mặt khác, được giảm bớt tham gia đảm nhận những công việc khác. Đặc biệt trong thời gian cực kỳ khó khăn này, nếu một nhân vật chính trị “ có vướng tỳ vết ” nào đó mà đang đảm nhận nhiệm vụ chính trị thì nguy hiểm rất cao ; trường học là nơi “ ẩn náu ” tốt nhất tránh được mọi cuộc va chạm, đối đầu, dị nghị. Những ai, đặc biệt là người nước ngoài, đảm nhận vị trí trong bộ máy Quốc tế Cộng sản thời kỳ này phải đối mặt với sự nguy hiểm của chiến dịch “ thanh trừng nội bộ ”. Nguyễn Ái Quốc không có danh sách trong bộ máy Quốc tế Cộng sản, không đảm nhận công việc cụ thể nào “ mà chỉ lo học hành ”.

Một yếu tố cực kỳ quan trọng, đó là tầm ảnh hưởng, tiếng tăm của Nguyễn Ái Quốc trên chính trường quốc tế. Khi xử lý vụ việc Nguyễn Ái Quốc, rõ ràng những người có trách nhiệm trong bộ máy Quốc tế Cộng sản luôn tỏ thái độ kính nể và thận trọng. Có những việc phải cử người ra nước ngoài để thẩm tra, xác minh. Ngay cả Vaxiliepna cũng phải thừa nhận : “ Tôi từng biết tiếng tăm của đồng chí Nguyễn trước khi làm việc trực tiếp với đồng chí ”.

Cũng phải thừa nhận rằng, ít người trong thời kỳ này khi có “ tỳ vết chính trị ” được thành lập Ban thẩm tra để giải quyết một cách thận trọng như trường hợp Nguyễn Ái Quốc. Phần lớn rơi vào trường hợp này thường bị xử lý “ tiền trảm hậu tấu ”.

Thời điểm khó khăn nhất là lúc bản lĩnh Nguyễn Ái Quốc tỏa sáng. Vì sao một số nhân vật lãnh đạo Đảng nhiều lần nhắc Nguyễn Ái Quốc viết bản tự chỉ trích về tư tưởng dân tộc chủ nghĩa, biệt phái tiểu tư sản, sai lầm về đấu tranh giai cấp... nhưng Nguyễn Ái Quốc không phản ứng, không giãi bày, chấp nhận nó trong im lặng. Nếu viết ra thành văn bản tức là chấp nhận thất bại, tự đầu hàng, biết đâu là cái cớ cho kẻ khác lợi dụng... Tư duy nhìn xa trông rộng của thiên tài là ở chỗ đó.

Lịch sử luôn luôn đúng. Hồ Chí Minh luôn đứng về phía lịch sử và làm nên lịch sử ở những thời khắc lịch sử.

BÁ NGỌC

CHÚ THÍCH :

1. Thư Ban lãnh đạo Hải Ngoại gửi Quốc tế Cộng Sản ngày 20-4-1935. Bút tích tiếng Pháp, ký hiệu lưu trữ 495-154-699.

2. Báo cáo của Vaxiliepna gửi Bộ Phương Đông, Vụ tổ chức cán bộ của Quốc tế Cộng sản ngày 29-6-1935. Ký hiệu lưu trữ 495-201-01 tờ số 154 đến 156.

3. Báo cáo giải trình của Vaxiliepna gửi ban Phương Đông và Vụ tổ chức cán bộ ký hiệu lưu trữ 495- 201-01 tờ số 143 đến 148.

4. Thư của Vụ tổ chức cán bộ gửi Viện nghiên cứu các vấn đề dân tộc thuộc địa đề ngày 8-2-1938, ký hiệu lưu trữ 495-201-01 tờ số 134.

NGUỒN : Tạp chí Xưa & Nay

số 438, tháng 10.2013

![[1] 1938, 6 tên gián điệp bí mật nhất của Trung Cộng, số 1 Hồ Tập Chương (Hồ Chí Minh) phụ trách Đông Dương, Lý Khắc Nông (李克農) Thứ trưởng kiêm Giám đốc Văn phòng Bát lộ quân, Khang Sanh (Kang Sheng) Bộ trưởng Bộ Xã hội, Tiền Tráng Phi (Qian Zhuangfei) UBND, Hồ Để (胡底) thư ký Trung ương Cục CPC, Long Đàm (Longtan) nằm vùng Quốc Dân Đảng. Nguồn: Tài liệu HuỳnhTâm.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEgHVdiVY7jV3u_twZEIxy3BLGUryz7lSG1qtVUr3w5CKNaHU-pwP7fpnCgRKCqRqtlJYUL6JouPS85bKZFoGZf9EwM9eJ-3nXaGwKmKNoQt_GLrRpriNyWw9av-DK8o3xSvaJDnic5bTIzG4P3hK9KarwGt1nIShmBMWmP9L5z30Ert=s0-d-e1-ft&h=418)